The Next Shortage Facing Young Homebuyers: Good Schools

Now, the same young homebuyers who must cope with bidding wars to buy a first home may face a shortage in another key resource: schools for their kids.

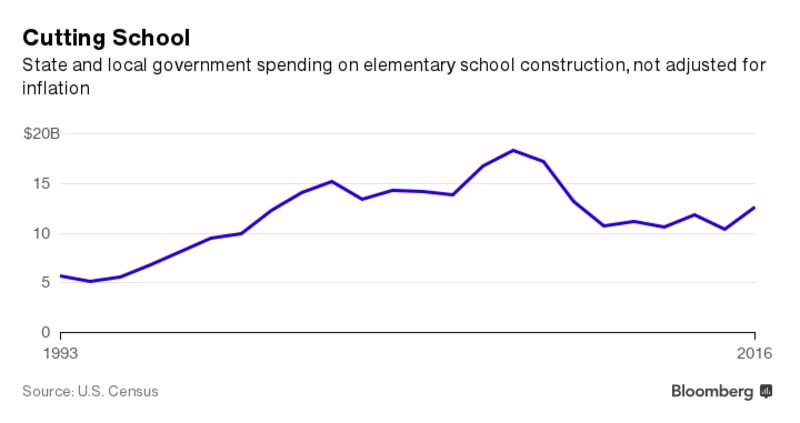

State and local governments spent $12.6 billion on elementary school construction in 2016, according to Census Bureau data—the highest amount in six years, but a 31 percent decrease compared with 2008, even before adjusting for inflation. Meanwhile, while construction spending has plummeted, enrollment has increased by four percent.

Most funding for school construction comes from local governments, said Alex Donahue, deputy director for policy and research at the 21st Century School Fund, a Washington-based nonprofit. With local finances continuing to suffer years after the collapse, there is less money for school funding in general, and facilities upgrades in particular.

“Spending declined during the recession mainly because 80 percent of that spending is local dollars, and the local governments didn’t have the money,” Donahue said.

The shortfalls were compounded by state and federal funding cuts to education. Thirty-five states provided less total funding per student for primary and secondary education in 2014 then they did in 2008, according to a report last year from the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) that covers the most recent available data. Those cutbacks were driven by lower income and payroll tax revenue during the recession.

Rather than raise taxes—an increasingly suicidal political option despite infrastructure needs—states sought to close budget shortfalls by reducing spending.

Those cuts placed a greater burden on local governments to pay for total education funding at a time when their ability to raise property tax revenue—an important source of school funding—was impaired by plummeting home values. Budget shortfalls forced school systems to defer maintenance on existing facilities and put off building new ones, said Elizabeth McNichol, a senior fellow at CBPP.

Compounding the problem, McNichol said, state and local governments have become more hesitant to borrow money, viewing the assumption of debt as being just as politically untenable as tax hikes. “It doesn’t really make sense at times when there’s low interest rates,” she said. “They’re missing a chance to catch up.”

“Debt,” she said, “has become a dirty word.”

Nationally, public schools need an additional $46 billion annually to maintain and update existing buildings and pay for new facilities, according to a 2016 report from the 21st Century School Fund. Only three states—Georgia, Florida, and Texas—exceeded the minimum capital construction and maintenance spending levels needed to uphold basic standards. Eighteen states spent less than 60 percent of the amount needed.

Meanwhile, because school funding is often driven by property tax revenue, the shortfalls expressed in the chart above aren’t distributed equally. A decade after the U.S. housing market began to implode, just 1 in 3 homes has recovered peak value, according to a recent study by Trulia. Quality of local schools, meanwhile, has long been a key selling point for house-hunters—part of a feedback loop that helps rich school districts get richer.

“If there’s a period of under-investment, particularly in places that haven’t recovered yet, that has implications for subsequent generations,” said Ralph McLaughlin, chief economist at Trulia. “That potentially is widening income equality for the next generation.”

Leave a Reply